- Home

- Paula Danziger

This Place Has No Atmosphere Page 11

This Place Has No Atmosphere Read online

Page 11

Dad’s also on a team in the lighter-than-air hockey league. They play in an area with reduced gravity. Everyone weighs less, including the players. Dad likes that a lot because he’s put on about ten pounds since he’s gotten here. Dehydrated food seems to agree with him . . . or maybe it was the extra brownie crumbs.

As for Hal, I think I really like him a lot. It’s so weird though. He’s not like any other boy that I’ve liked before or thought I would like. It’s scary that my feelings could be so strong if I’d let them be. He’s so different from all the other guys I’ve dated. I don’t want to talk about this anymore. It makes me too nervous to feel so close to him.

I’m not sure of a lot of things.

It sure is hard growing up.

It sure was hard being a kid.

Is it going to be hard being a grown-up? (Don’t tell me. I don’t think I want to know the answer.)

I really wish you could be here to see the play. It’s going to be terrific.

To answer your other question: I don’t know anymore whether I’m going to leave at the end of the year or not. I’m not sure where I belong anymore. It’s another thing that I don’t want to think about right now.

What I do want to think about is how much I love you both.

Miss you,

CHAPTER 31

“Break a leg!” Tolin sticks his head into the green room and smiles at the cast before going back to the prop room.

“How come he said that?” Karlena asks. “I thought he liked us.”

“It’s an old theater tradition,” I tell her.

“Break an ankle!” Someone yells out.

“A fingernail!”

“A toenail!”

“An armpit!”

“A pimple!”

“That’s gross!”

“Break a gross!”

The cast is definitely getting hysterical.

The play begins in less than an hour.

It’s our first performance.

Tomorrow we do a matinee, so that the little kids can see it without staying up too late, and then we have a final performance tomorrow night. That way, everyone on the moon who wants to can see the play.

I look around the room.

Tucker and Starr are going over their lines again and again.

She’s biting her fingernails so much that soon she’ll have to start on Tucker’s fingernails.

Karlena is looking very nervous, taking in little gulps of air.

Kael brings her a glass of water, and then they kiss for a very long time.

I’m surprised that she can breathe at all after that.

Watching them makes me feel lonely.

People are pacing around the room.

I sit in my chair, trying to be calm and centered.

It’s not easy.

Vern walks in and says, “There are eighty billion people out there.”

Either he’s exaggerating or a lot of aliens from other planets have just rocketed in for their first Off-Off-Off-Off-Off-Off-Off-Broadway play.

Hal comes over and kneels down in front of me. “Do you want company or do you want to be alone? Since I’m already in this position, would you like me to propose to you?”

I look at him. “Just hold my hand for a minute.”

He does, and it helps calm me down.

“Thanks.” I smile at him. “And how are you doing?”

“Fine, since I don’t have to act. Aurora, about the cast party tomorrow night: I know we’ll both be there, but do you want to go as my date?”

I think about it for a minute.

He starts to joke. “If you don’t want to go as my date, you can go as my fig . . . or as my raisin. I mean, after the play you won’t be Mrs. Gibbs anymore, so going out with me wouldn’t be bigamy or whatever it’s called.” He’s definitely not in practice asking for a date. “Or we could go separately. Listen, maybe this wasn’t the right time to ask you.”

I look at him and smile. “Yes. I’d love to be your date. It gives me a raisin to really look forward to the cast party. Then the thought of having a great time won’t be a figment of my imagination.”

He groans at my puns and grins at the same time.

Mr. Wilcox arrives. “Please. Everyone out but my actors.”

Hal kisses my cheek. “See you later.”

Everyone but the cast leaves, and Mr. Wilcox looks at us. “All right. In just a few minutes, you’ll be having a great time.”

“Why? Did someone call off the play?” Tucker asks.

There’s nervous laughter.

Mr. Wilcox says softly, “You’ve done the hardest work already. Now I want you to take a deep breath and get into character.”

Inhaling deeply, I try to get centered.

I become Mrs. Gibbs. I think about waiting for my husband, Dr. Gibbs, who has gone out to deliver a baby. I think about having to wake my two kids up soon and about preparing breakfast for everyone.

I think about being in 1901, not 2057.

“Take your places,” Mr. Wilcox calls out. “And don’t look at the audience.”

We take our places.

I try not to look at the audience.

Our Town begins.

CHAPTER 32

The audience applauds like crazy for the second night in a row. We are a hit! There are six curtain calls. Everyone thinks we’re great.

Mr. Wilcox was right, even though I hate to admit it. Mrs. Gibbs was the right part for me.

After the last curtain call, Kael steps forward to speak for the cast and crew. “We want to thank Mr. Wilcox and April Brown for all their help in putting this play on and want to give them a token of our appreciation.”

Hal comes on stage, carrying a director’s chair with Mr. Wilcox’s name printed on it in moon-day-glow colors.

Starr hands April a neon necklace with a silvery moon part and a red sparkling heart.

Everyone in the cast and crew chipped in. We had the presents sent up on the space shuttle.

April looks happy and says, “Thanks. This has really been one of the best experiences of my life.”

The audience applauds and cheers April, and Tolin whistles loudly.

It’s Mr. Wilcox’s turn next.

He talks about how proud he is of everyone. Then he says, “I want to take this opportunity to especially thank the two young people who had the idea, got the funds, and have worked very hard in different areas to make this production a success. Let’s have a special hand for Hal Brenner and Aurora Williams.”

Hal and I look at each other.

He takes my hand in his and says, “This really is a very special hand.”

We step forward and there’s a lot of applause.

I’m so happy and proud.

Mr. Wilcox says, “I’m probably crazy to let myself in for all this work again, but I can’t let the director’s chair go to waste. So let’s start an official acting company and put on more productions.”

The crowd goes wild.

So do the cast and crew. We hug and kiss each other as the audience begins to leave.

Then it’s all over. All those months of work, and in two days it’s over.

I feel a little empty.

“Cast party,” Mr. Wilcox calls out. “Strike the set. Get out of costume and be in the rec room in twenty minutes.”

We take the set down and apart. Soon there is no more Grover’s Corners and Our Town. It’s back to the twenty-first century and “Our Moon.”

Heading to the costume room, Karlena and I smile at each other.

“You were great,” I say, meaning it.

“You too.” She hugs me. “Thanks for all the help. I’m so glad that we’ve become friends.”

“Me too.” If I were back on earth, I think that I’d be homesick for her and the other kids on the moon. I wish that it was the future and that someone had invented a way to be in two places at the same time.

Starr comes running up. “Firstly, I want to know when we b

egin the next play, and twoly, I want to know if you think I’m good enough to get a part in it.”

“I don’t know when we start, but I do know that you’re getting better. It’ll just depend on what the play is,” I tell her. “And Starr, twoly is not a word and I’m not sure that firstly is either.”

“Now it is,” she says, and begins to sing “I love you twoly.”

Being in the play has definitely gone to Starr’s brain.

We go to the costume room and change.

Emily Doowinkle recites:

“Play.

Day.

Cast.

Last.”

I wish we’d taken up a collection to send her to poetry school.

When I go back to the stage area, Mr. Wilcox and Hal are talking.

As I join them, Hal hands me a rose.

“Thanks,” I say. “I bet this cost you a whole month’s allowance.”

He shakes his head. “I promised Mr. Conway I would help him to fertilize the greenhouse.”

I cross my eyes and ask, “How?”

He grins. “We’re using chemical fertilizers, silly.”

Mr. Wilcox changes the subject. “Aurora, before the cast party starts, I want you to know that I think that you’ve grown tremendously, and not just as an actress.”

“Thanks,” I say softly, knowing what he means.

He continues. “You’ve also done a great job at school with the Eaglettes. They really love you.”

“I love them too.” I smile.

“That makes me want to be an Eaglette again,” Hal says.

“All this praise makes me sound like a Goody Two-shoes,” I tell them.

Both of them say, “NO!”

Mr. Wilcox says, “Maybe when you stop mentioning earth every five minutes.”

“She used to say it every three minutes, so she’s improving,” Hal says. “What drives me nuts is hearing the name Matthew uttered constantly.”

I ask, “What if I say ‘ER THanks for the compliment, but I need assistance with MATH. YOU will help me, won’t you?’ Is that allowed?”

“She said MATH YOU again.” Hal slaps his hand on his forehead.

Mr. Wilcox shakes his head. “And ER THe. I guess she’s not quite turned into Ms. Two-shoes yet.”

Mr. Wilcox leaves us and Hal touches my hair. I kiss him on the cheek.

“I thought this was a date,” he says.

I kiss him on the lips.

“That’s more like it,” he says, when we stop to breathe.

We kiss again.

“Aurora.” It’s my father’s voice.

Hal and I jump apart.

Both of our faces are the color of my rose.

My parents and his are standing there.

How embarrassing, but what fun.

My mother smiles. “I’m very proud of you.”

“Me too,” my father says.

“We are too,” the Brenners agree. “You were terrific, both of you.”

Hal laughs. “Did you notice that the chairs were always in the right place? My job.”

His father says, “I also noticed all the nights that you were up late working on the play.”

Hal looks pleased.

“We have to go to the cast party,” Hal reminds them.

We say good-bye to our parents and leave.

As Hal and I walk along, I think about how things have changed since I came to the moon. I know I’m going to have to make some important decisions soon.

But not tonight.

Tonight’s a celebration.

CHAPTER 33

Dear Grandma Jennifer and Grandpa Josh,

This is not an easy letter to write.

I won’t be coming back to earth this year after all. l’ve decided to graduate from Da Vinci School and to return to earth for college. It was not an easy decision, but I know it’s the right one. I wouldn’t fit in at my old school anymore. I’m also not sure that I want to make another change so soon, especially since I’m used to this place now and like a lot of people here more than I ever thought I could.

Also, the acting company is beginning and I really want to be an active member of it. I can’t wait.

Another thing, for most of my life I’ve always thought that having a boyfriend was the most important thing in the world. Now I know there are a lot of other things that are also important. That doesn’t mean that I don’t care about Hal—I do. Actually, I care more about him than about any other boy I’ve ever gone out with. But who knows what will happen? For now, though, it’s very special. (When you started going out with Grandpa, did your whole body tingle? Does it still? This is the stuff that the sex-info computer disk never discusses. I have a feeling I’m getting ready to graduate to Disc II. I’m afraid to think about what’s on Disc V.)

The main reason I’m sorry I’m not coming home right now is because I love and miss you so much. We will see each other next year, though. I promise. I’m absolutely, positively not staying up here forever. This place really has no atmosphere. I still want to be an actress and I need to see things and have experiences that I can’t have up here. I’ve seen the moon. Now I want to see Paris.

I guess that catches you up on just about everything I’m thinking about. Don’t be too upset.

I’ll be back on earth soon.

Maybe someday I’ll be a star.

Today I’ll just live among them.

Love,

Text copyright © 1974 by Paula Danziger

CHAPTER 1

I hate my father. I hate school. I hate being fat. I hate the principal because he wanted to fire Ms. Finney, my English teacher.

My name is Marcy Lewis. I’m thirteen years old and in the ninth grade at Dwight D. Eisenhower Junior High.

All my life I’ve thought that I looked like a baby blimp with wire-frame glasses and mousy brown hair. Everyone always said that I’d grow out of it, but I was convinced that I’d become an adolescent blimp with wire-frame glasses, mousy brown hair, and acne.

My life is not easy. I know I’m not poor. Nobody beats me. I have clothes to wear, my own room, a stereo, a TV, and a push-button phone. Sometimes I feel guilty being so miserable, but middle-class kids have problems too.

Mom always made me go to tap and ballet lessons. She said that they’d make me more graceful. When it came time for the recital, I accidentally sat on the record that I was supposed to dance to, and broke it. I had to hum along with the tap dancing. I sing as badly as I dance. It was a disaster.

Father says that girl children should be born at the age of eighteen and married off immediately.

Stuart, my four-year-old brother, wants to be my best friend so that I can help him put orange pits in a hole in his teddy bear’s head.

I’m flat-chested. I used to buy training bras and put tucks in them.

I never had any friends, except Nancy Sheridan. She’s very popular, but her mother and mine are PTA officers and old friends, so I always figured that Mrs. Sheridan made her talk to me—Beauty and the Blimp.

School is a bummer. The only creative writing I could do was anonymous letters to the Student Council suggestion box. Lunches are lousy. We never get past the First World War in history class. We never learned anything good, at least not till Ms. Finney came along.

So my life is not easy.

The thing with Ms. Finney is what I want to talk about. She took over for Mr. Edwards, our first English teacher. He left after the first month. One rumor is that he had a nervous breakdown in the faculty lounge while correcting a test on noun clauses. Another is that he had to go to a home for unwed fathers in Secaucus, New Jersey. I personally think that he realized that he was a horrible teacher, so he took a job somewhere as a principal or a guidance counselor.

When Mr. Edwards left, we got a whole bunch of substitutes. None of them lasted more than two days. That’ll teach the school to group all the smart kids in one class. We were indestructible.

The entire class dropped books

, pencils, and pens at an assigned time. Someone put bubble gum in the pencil sharpener. Nancy pulled her fainting act. We made up names and wrote them on the attendance list. All the desks got turned around. Mr. Stone, the principal, kept coming in and yelling.

And then Ms. Finney came.

CHAPTER 2

Celeste Sanders was the first to spread the news.

“Hey, we got a new English teacher. A real one, not a sub. First-period class says she looks like a kid.”

“A new one. Let’s walk in backwards.”

“Everyone give a wrong name.”

“Let’s show her who’s boss.”

Everybody rushed down the halls and into class. Some of the guys started to make and throw paper airplanes. Alan Smith played “Clementine” on his harmonica. He’d learned it from the instructions on a Good and Plenty box. Jim Heston played the Good and Plenty box, and Ted Martin played a comb. There was applause and cheering after the performance. At 1:15 the coughing started. A few kids didn’t do anything, but I did. I really didn’t like what was happening, but if you’re a blimp with fears of impending acne, you go along with the crowd.

Ms. Finney just sat there. She was young and wore a long denim skirt, a turtleneck jersey and had on weird jewelry—giant earrings that hung down to her shoulders, and a macrame necklace. She didn’t smile or yell or cry or read a paper or do any of the things that teachers normally do when a class gets out of hand. She just sat there and looked at everybody.

Finally it got quiet. Everyone started to squirm. It was really creepy after a while.

“O.K. Give her a chance,” someone muttered.

We all looked around to see who was talking. It was Joel Anderson, the smartest kid in the class. When almost everybody else would be fooling around, he would sit there reading a book. Some of the kids thought he was a little weird, but everybody usually listened to him.

He put his book down, looked at Ms. Finney, and said, “Are you going to teach us anything?”

Somebody giggled.

The class got very quiet.

I looked at Joel and thought how brave and smart and cute he was. We’d been in the same classes since kindergarten, but I hadn’t said more to him than “Hi” and “What’s the homework assignment?” I didn’t like to embarrass anyone by having them be seen talking to me.

Amber Brown Horses Around

Amber Brown Horses Around Amber Brown Is Green with Envy

Amber Brown Is Green with Envy I, Amber Brown

I, Amber Brown Amber Brown Is Tickled Pink

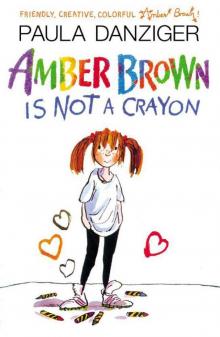

Amber Brown Is Tickled Pink Amber Brown Is Not a Crayon

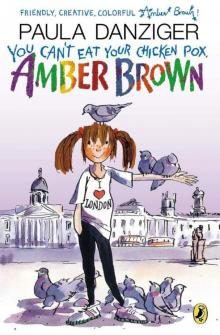

Amber Brown Is Not a Crayon You Can't Eat Your Chicken Pox, Amber Brown

You Can't Eat Your Chicken Pox, Amber Brown This Place Has No Atmosphere

This Place Has No Atmosphere The Cat Ate My Gymsuit

The Cat Ate My Gymsuit Amber Brown Goes Fourth

Amber Brown Goes Fourth Forever Amber Brown

Forever Amber Brown The Divorce Express

The Divorce Express It's an Aardvark-Eat-Turtle World

It's an Aardvark-Eat-Turtle World Amber Brown Wants Extra Credit

Amber Brown Wants Extra Credit Amber Brown Is on the Move

Amber Brown Is on the Move Amber Brown Is Feeling Blue

Amber Brown Is Feeling Blue Amber Brown Sees Red

Amber Brown Sees Red There's a Bat in Bunk Five

There's a Bat in Bunk Five